The Historic Round Rock Collection

The Santa Fe Expedition

The Historic Round Rock Collection is a project documenting Round Rock’s history, funded in part with a grant from the Texas Historical Commission. These pages are adapted from the original 1991 print version.

Texas President Mirabeau Lamar wanted to open trade with Santa Fé, then part of Mexico, to revitalize the weak Texas economy (Scarbrough 98). William Jones wrote Lamar in 1839, advising that the President sponsor an expedition of traders with a protective military escort to Santa Fé. He argued that:

Immense profits must result from [the mission] and the introduction of 75 or 100 thousand dollars of specie1 thro’ the Colorado Valley will give confidence to individual enterprise and the route will soon be lined with traders able to protect themselves, who will introduce the riches of New Mexico into the lap of Texas (letter of William J. Jones of February 8, 1839, quoted in Christian 106).

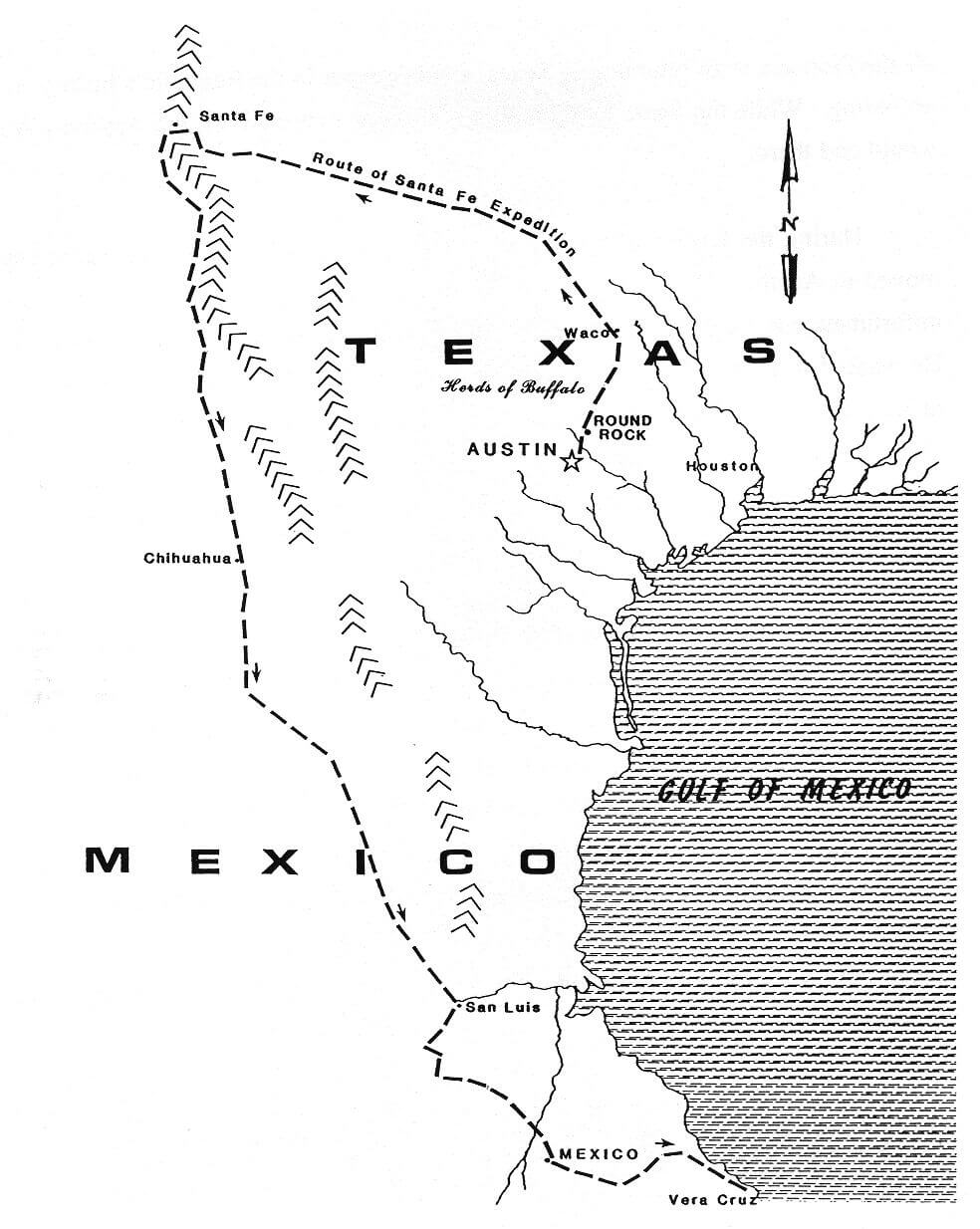

Others saw even greater potential. Santa Fé was a major shipping point between the United States and the interior of Mexico. In the late 1830s, an estimated four million dollars of U.S. trade passed through Santa Fé, most of it routed from Saint Louis. It was thought that if a military road was built to the city, trade could be diverted through Texas. The ports of Texas were closer than St. Louis and offered good facilities for shipping to major cities (Christian 108). t the time, though, the army was too busy fighting hostile Native Americans and the treasury was too short of funds for any action to be taken (Ibid. 111). However, Lamar liked the idea and spoke favorably of an expedition many times during 1839 and 1840. In January of 1841, the Texas legislature considered, then narrowly rejected, two bills authorizing Lamar to open communication with Santa Fé and to send an expedition to the city (Ibid. 114).

In February, despite the Congressional rebuff, Lamar began organizing a volunteer expedition to be headed by General Hugh McLeod. The call for volunteers brought men and boys from all over Texas to Austin. From there they moved north to the main camp, Camp Cazneau, near Kenney Fort (Ibid.). Some members of the expedition camped as long as a month on Brushy Creek (Ibid. 99). The last group to join the mission left Austin on June 18 with President Lamar, who travelled to Camp Cazneau to address the Pioneers, as the group was called, on the eve of their departure (Ibid. 114).

Thomas Falconer, a member of the expedition, described his trip from Austin to Brushy Creek:

“I left Austin upon the 17th of June, and joined the expedition which was then encamped at Brushy, about 12 miles off. About half way there was a grove of oak trees, and a short distance beyond was an extensive plain divided by a long dark line of trees. The camp was among the trees. Close to it was a spring of water coming from the limestone rock…” (Falconer 77-78).

When he arrived, over three hundred men had gathered to take part in the adventure to open trade with Mexico through Santa Fé (Scarbrough 98). General McLeod led a company of 270 soldiers who had volunteered for the mission. The remaining fifty members were an odd combination of tourists, merchants and the Commissioners representing the government of Texas (Christian 114-115). On the morning of Sunday, July 20, 1841, President Lamar gave a “thrilling, patriotic” speech and set the expedition on its way (“Some Early…” 79). They followed the Double File Trail north, from Palm Valley to Towns Mill, just to the west of present day Weir. They camped the first night on the San Gabriel River; some of the volunteers passed the time fishing and shooting alligators (Scarbrough 99-100). The troop was poorly provisioned for what was expected to be a 500-mile journey but turned into a 1000-mile odyssey. Despite being equipped with twenty wagons loaded with food and supplies and a small herd of cattle, two days into the journey the Pioneers were forced to send for more supplies (Scarbrough 99). This foreshadowed the problems the expedition was to face throughout the journey.

Although the mission was publicly commissioned to open communication and trade with Santa Fé, President Lamar had other plans (Falconer 76). His representatives, Colonel William G. Cooke, J. Antonio Navarro and Dr. Richard Brenham, carried with them an address to the people of Santa Fé. President Lamar wrote to “the Inhabitants of Santa Fe:”

“Believing that you are the friends of liberty, and will duly appreciate the motives by which we are actuated, we have appointed commissioners to make known to you… the general desire of the citizens of this Republic to receive the people of Santa Fe, as a portion of the national family, and to give them all the protection which they themselves enjoy. This union, however, to make it agreeable to this Government, must be altogether voluntary on your part; and based on mutual interest, confidence and affection. Should you, therefore, in view of the whole matter be willing to avail yourselves of this opportunity to secure your own prosperity, as well as that of your descendants, by a prompt, cheerful and unanimous adherence to the Government of this republic we invite you to a full and unreserved intercourse and communication with our commissioners… The only change we desire to effect in your affairs, is such as we wrought in our own when we broke our fetters and established our freedoms; a change which was well worth the price we paid; and the blessings of which we are ready now to extend to you at the sacrifice (sic) of our own lives and fortunes…” (Wallace and Vigness 138).

The President’s address was misleading. The commissioners and General McLeod were instructed to take possession of the public property in Santa Fé and appoint local residents to control them for Texas (Christian 116). Then they were to convince the citizens of Santa Fé that it was in their interest to join Texas and to have them do so voluntarily. At all costs, there was to be no violence. One official wrote that:

“The President, anxious as he is to have our National flag acknowledged in Santa Fé (sic) does not consider it expedient at this time to force it upon that portion of the Republic. If the Mexican authorities are prepared to defend the place with arms, and if you can satisfy yourselves that they will be supported by the mass of the people, no good result can come from risking a battle; for if our arms are successful, a strong Military force would be necessary to hold possession of the place… In this case therefore, you will not be authorized to risk a battle.” (quoted in Christian 117)

The volunteers were not aware that President Lamar wished Santa Fé to secede from Mexico and join the Republic of Texas (Falconer 76), and they paid a high price for their ignorance. The expedition, twice as long as expected, beset by drought and disease, assailed by hostile Native Americans, hampered by supply shortages, and divided into separate groups by infighting, ended in disaster (Scarbrough 100-101). Perhaps, not surprisingly, the New Mexico governor arrested the small groups as they straggled into Santa Fé. The Pioneers surrendered peaceably, and upon giving up they were forced marched an additional 2000 miles to Mexico City where the surviving members were released.

Notes

1 Specie is money in coin form. return to text

Works Cited

Christian, Asa Kyrus. Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar. Doctoral Thesis, University of Pennsylvania. Von Boekmann-Jones Co., Printers, Austin, Texas: 1922.

Falconer, Thomas. Letters and Notes on the Texas Santa Fe Expedition 1841-1842. Dauber & Pine Bookshops, Inc., New York City: 1930.

Scarborough, Clara Stearns. 1973. Land of Good Water, Takachue Pouetsu: A Williamson County, Texas History. Williamson County Sun Publishers, Georgetown, Texas.

“Some Early Williamson County History” in Frontier Times. No date. Photocopy in Round Rock Public Library. Article reprinted from Williamson County Sun (Georgetown) April 7, 1936. Original W. K. Makemson. Historical Sketch of First Settlement and Organization of Williamson County. Sun Print, Georgetown, Texas. 1904.